15. NumPy vs Numba vs JAX#

In the preceding lectures, we’ve discussed three core libraries for scientific and numerical computing:

Which one should we use in any given situation?

This lecture addresses that question, at least partially, by discussing some use cases.

Before getting started, we note that the first two are a natural pair: NumPy and Numba play well together.

JAX, on the other hand, stands alone.

When considering each approach, we will consider not just efficiency and memory footprint but also clarity and ease of use.

In addition to what’s in Anaconda, this lecture will need the following libraries:

!pip install quantecon jax

GPU

This lecture is accelerated via hardware that has access to a GPU and target JAX for GPU programming.

Free GPUs are available on Google Colab. To use this option, please click on the play icon top right, select Colab, and set the runtime environment to include a GPU.

Alternatively, if you have your own GPU, you can follow the instructions for installing JAX with GPU support.

If you would like to install JAX running on the cpu only you can use pip install jax[cpu]

We will use the following imports.

import random

import numpy as np

import quantecon as qe

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from mpl_toolkits.mplot3d.axes3d import Axes3D

from matplotlib import cm

import jax

import jax.numpy as jnp

15.1. Vectorized operations#

Some operations can be perfectly vectorized — all loops are easily eliminated and numerical operations are reduced to calculations on arrays.

In this case, which approach is best?

15.1.1. Problem Statement#

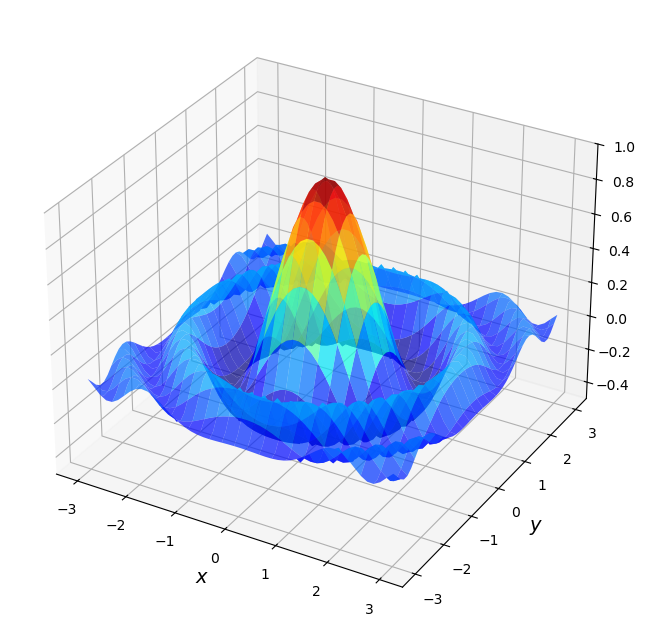

Consider the problem of maximizing a function

For

Here’s a plot of

def f(x, y):

return np.cos(x**2 + y**2) / (1 + x**2 + y**2)

xgrid = np.linspace(-3, 3, 50)

ygrid = xgrid

x, y = np.meshgrid(xgrid, ygrid)

fig = plt.figure(figsize=(10, 8))

ax = fig.add_subplot(111, projection='3d')

ax.plot_surface(x,

y,

f(x, y),

rstride=2, cstride=2,

cmap=cm.jet,

alpha=0.7,

linewidth=0.25)

ax.set_zlim(-0.5, 1.0)

ax.set_xlabel('$x$', fontsize=14)

ax.set_ylabel('$y$', fontsize=14)

plt.show()

For the sake of this exercise, we’re going to use brute force for the maximization.

Evaluate

Return the maximum of observed values.

Just to illustrate the idea, here’s a non-vectorized version that uses Python loops.

grid = np.linspace(-3, 3, 50)

m = -np.inf

for x in grid:

for y in grid:

z = f(x, y)

if z > m:

m = z

15.1.2. NumPy vectorization#

If we switch to NumPy-style vectorization we can use a much larger grid and the code executes relatively quickly.

Here we use np.meshgrid to create two-dimensional input grids x and y such

that f(x, y) generates all evaluations on the product grid.

(This strategy dates back to Matlab.)

grid = np.linspace(-3, 3, 3_000)

x, y = np.meshgrid(grid, grid)

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

z_max_numpy = np.max(f(x, y))

print(f"NumPy result: {z_max_numpy}")

0.25463414 seconds elapsed

NumPy result: 0.9999979986680024

In the vectorized version, all the looping takes place in compiled code.

Moreover, NumPy uses implicit multithreading, so that at least some parallelization occurs.

Note

If you have a system monitor such as htop (Linux/Mac) or perfmon (Windows), then try running this and then observing the load on your CPUs.

(You will probably need to bump up the grid size to see large effects.)

The output typically shows that the operation is successfully distributed across multiple threads.

(The parallelization cannot be highly efficient because the binary is compiled

before it sees the size of the arrays x and y.)

15.1.3. A Comparison with Numba#

Now let’s see if we can achieve better performance using Numba with a simple loop.

import numba

@numba.jit

def compute_max_numba(grid):

m = -np.inf

for x in grid:

for y in grid:

z = np.cos(x**2 + y**2) / (1 + x**2 + y**2)

if z > m:

m = z

return m

grid = np.linspace(-3, 3, 3_000)

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

compute_max_numba(grid)

0.28494620 seconds elapsed

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

compute_max_numba(grid)

0.13257146 seconds elapsed

Depending on your machine, the Numba version can be a bit slower or a bit faster than NumPy.

On one hand, NumPy combines efficient arithmetic (like Numba) with some multithreading (unlike this Numba code), which provides an advantage.

On the other hand, the Numba routine uses much less memory, since we are only working with a single one-dimensional grid.

15.1.4. Parallelized Numba#

Now let’s try parallelization with Numba using prange:

Here’s a naive and incorrect attempt.

@numba.jit(parallel=True)

def compute_max_numba_parallel(grid):

n = len(grid)

m = -np.inf

for i in numba.prange(n):

for j in range(n):

x = grid[i]

y = grid[j]

z = np.cos(x**2 + y**2) / (1 + x**2 + y**2)

if z > m:

m = z

return m

Usually this returns an incorrect result:

z_max_parallel_incorrect = compute_max_numba_parallel(grid)

print(f"Incorrect parallel Numba result: {z_max_parallel_incorrect}")

print(f"NumPy result: {z_max_numpy}")

Incorrect parallel Numba result: -inf

NumPy result: 0.9999979986680024

The incorrect parallel implementation typically returns -inf (the initial value of m) instead of the correct maximum value of approximately 0.9999979986680024.

The reason is that the variable

When multiple threads try to read and write m simultaneously, they interfere with each other, causing a race condition.

This results in lost updates—threads read stale values of m or overwrite each other’s updates—and the variable often never gets updated from its initial value of -inf.

Here’s a more carefully written version.

@numba.jit(parallel=True)

def compute_max_numba_parallel(grid):

n = len(grid)

row_maxes = np.empty(n)

for i in numba.prange(n):

row_max = -np.inf

for j in range(n):

x = grid[i]

y = grid[j]

z = np.cos(x**2 + y**2) / (1 + x**2 + y**2)

if z > row_max:

row_max = z

row_maxes[i] = row_max

return np.max(row_maxes)

Now the code block that for i in numba.prange(n) acts over is independent

across i.

Each thread writes to a separate element of the array row_maxes.

Hence the parallelization is safe.

Here’s the timings.

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

compute_max_numba_parallel(grid)

1.18451452 seconds elapsed

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

compute_max_numba_parallel(grid)

0.03486371 seconds elapsed

If you have multiple cores, you should see at least some benefits from parallelization here.

For more powerful machines and larger grid sizes, parallelization can generate major speed gains, even on the CPU.

15.1.5. Vectorized code with JAX#

In most ways, vectorization is the same in JAX as it is in NumPy.

But there are also some differences, which we highlight here.

Let’s start with the function.

@jax.jit

def f(x, y):

return jnp.cos(x**2 + y**2) / (1 + x**2 + y**2)

As with NumPy, to get the right shape and the correct nested for loop

calculation, we can use a meshgrid operation designed for this purpose:

grid = jnp.linspace(-3, 3, 3_000)

x_mesh, y_mesh = np.meshgrid(grid, grid)

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

z_max = jnp.max(f(x_mesh, y_mesh)).block_until_ready()

0.36362576 seconds elapsed

Let’s run again to eliminate compile time.

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

z_max = jnp.max(f(x_mesh, y_mesh)).block_until_ready()

0.01939678 seconds elapsed

Once compiled, JAX is significantly faster than NumPy due to GPU acceleration.

The compilation overhead is a one-time cost that pays off when the function is called repeatedly.

15.1.6. JAX plus vmap#

There is one problem with both the NumPy code and the JAX code:

While the flat arrays are low-memory

grid.nbytes

12000

the mesh grids are memory intensive

x_mesh.nbytes + y_mesh.nbytes

72000000

This extra memory usage can be a big problem in actual research calculations.

Fortunately, JAX admits a different approach using jax.vmap.

15.1.6.1. Version 1#

Here’s one way we can apply vmap.

# Set up f to compute f(x, y) at every x for any given y

f_vec_x = lambda y: f(grid, y)

# Create a second function that vectorizes this operation over all y

f_vec = jax.vmap(f_vec_x)

Now f_vec will compute f(x,y) at every x,y when called with the flat array grid.

Let’s see the timing:

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

z_max = jnp.max(f_vec(grid))

z_max.block_until_ready()

0.10907602 seconds elapsed

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

z_max = jnp.max(f_vec(grid))

z_max.block_until_ready()

0.00109720 seconds elapsed

By avoiding the large input arrays x_mesh and y_mesh, this vmap version uses far less memory.

When run on a CPU, its runtime is similar to that of the meshgrid version.

When run on a GPU, it is usually significantly faster.

In fact, using vmap has another advantage: It allows us to break vectorization up into stages.

This leads to code that is often easier to comprehend than traditional vectorized code.

We will investigate these ideas more when we tackle larger problems.

15.1.7. vmap version 2#

We can be still more memory efficient using vmap.

While we avoid large input arrays in the preceding version,

we still create the large output array f(x,y) before we compute the max.

Let’s try a slightly different approach that takes the max to the inside.

Because of this change, we never compute the two-dimensional array f(x,y).

@jax.jit

def compute_max_vmap_v2(grid):

# Construct a function that takes the max along each row

f_vec_x_max = lambda y: jnp.max(f(grid, y))

# Vectorize the function so we can call on all rows simultaneously

f_vec_max = jax.vmap(f_vec_x_max)

# Call the vectorized function and take the max

return jnp.max(f_vec_max(grid))

Here

f_vec_x_maxcomputes the max along any given rowf_vec_maxis a vectorized version that can compute the max of all rows in parallel.

We apply this function to all rows and then take the max of the row maxes.

Let’s try it.

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

z_max = compute_max_vmap_v2(grid).block_until_ready()

0.24891353 seconds elapsed

Let’s run it again to eliminate compilation time:

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

z_max = compute_max_vmap_v2(grid).block_until_ready()

0.00040984 seconds elapsed

If you are running this on a GPU, as we are, you should see another nontrivial speed gain.

15.1.8. Summary#

In our view, JAX is the winner for vectorized operations.

It dominates NumPy both in terms of speed (via JIT-compilation and parallelization) and memory efficiency (via vmap).

Moreover, the vmap approach can sometimes lead to significantly clearer code.

While Numba is impressive, the beauty of JAX is that, with fully vectorized operations, we can run exactly the same code on machines with hardware accelerators and reap all the benefits without extra effort.

Moreover, JAX already knows how to effectively parallelize many common array operations, which is key to fast execution.

For almost all cases encountered in economics, econometrics, and finance, it is far better to hand over to the JAX compiler for efficient parallelization than to try to hand code these routines ourselves.

15.2. Sequential operations#

Some operations are inherently sequential – and hence difficult or impossible to vectorize.

In this case NumPy is a poor option and we are left with the choice of Numba or JAX.

To compare these choices, we will revisit the problem of iterating on the quadratic map that we saw in our Numba lecture.

15.2.1. Numba Version#

Here’s the Numba version.

@numba.jit

def qm(x0, n, α=4.0):

x = np.empty(n+1)

x[0] = x0

for t in range(n):

x[t+1] = α * x[t] * (1 - x[t])

return x

Let’s generate a time series of length 10,000,000 and time the execution:

n = 10_000_000

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

x = qm(0.1, n)

0.16079402 seconds elapsed

Let’s run it again to eliminate compilation time:

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

x = qm(0.1, n)

0.07165647 seconds elapsed

Numba handles this sequential operation very efficiently.

Notice that the second run is significantly faster after JIT compilation completes.

Numba’s compilation is typically quite fast, and the resulting code performance is excellent for sequential operations like this one.

15.2.2. JAX Version#

Now let’s create a JAX version using lax.scan:

(We’ll hold n static because it affects array size and hence JAX wants to specialize on its value in the compiled code.)

from jax import lax

from functools import partial

cpu = jax.devices("cpu")[0]

@partial(jax.jit, static_argnums=(1,), device=cpu)

def qm_jax(x0, n, α=4.0):

def update(x, t):

x_new = α * x * (1 - x)

return x_new, x_new

_, x = lax.scan(update, x0, jnp.arange(n))

return jnp.concatenate([jnp.array([x0]), x])

This code is not easy to read but, in essence, lax.scan repeatedly calls update and accumulates the returns x_new into an array.

Note

Sharp readers will notice that we specify device=cpu in the jax.jit decorator.

The computation consists of many very small lax.scan iterations that must run sequentially, leaving little opportunity for the GPU to exploit parallelism.

As a result, kernel-launch overhead tends to dominate on the GPU, making the CPU a better fit for this workload.

Curious readers can try removing this option to see how performance changes.

Let’s time it with the same parameters:

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

x_jax = qm_jax(0.1, n).block_until_ready()

0.12644219 seconds elapsed

Let’s run it again to eliminate compilation overhead:

with qe.Timer(precision=8):

x_jax = qm_jax(0.1, n).block_until_ready()

0.06671596 seconds elapsed

JAX is also efficient for this sequential operation.

Both JAX and Numba deliver strong performance after compilation, with Numba typically (but not always) offering slightly better speeds on purely sequential operations.

15.2.3. Summary#

While both Numba and JAX deliver strong performance for sequential operations, there are significant differences in code readability and ease of use.

The Numba version is straightforward and natural to read: we simply allocate an array and fill it element by element using a standard Python loop.

This is exactly how most programmers think about the algorithm.

The JAX version, on the other hand, requires using lax.scan, which is significantly less intuitive.

Additionally, JAX’s immutable arrays mean we cannot simply update array elements in place, making it hard to directly replicate the algorithm used by Numba.

For this type of sequential operation, Numba is the clear winner in terms of code clarity and ease of implementation, as well as high performance.